The Psychology of Space Exploration: A Review — Part 2

by Larry Klaes, space exploration enthusiast, science journalist, SF aficionado.

Note: this is a companion piece to Those Who Never Got to Fly.

To give some examples of what I feel is missing and limited in representation in Psychology of Space Exploration, there is but a brief mention of what author Frank White has labeled the “Overview Effect”. As the book states, this is the result of “truly transformative experiences [from flying in space] including sense of wonder and awe, unity with nature, transcendence, and universal brotherhood.”

Clearly this is a very positive reaction to being in space, one which could have quite helpful benefits for those who are exploring the Universe. The Overview Effect might also have an ironic down side, one where a working astronaut might become so caught up in the “wonder and awe” of the surrounding Cosmos away from Earth that he or she could miss a critical mission operation or even forget what they were originally meant to do. Mercury astronaut Scott Carpenter may have been one of the earliest “victims” of the Overview Effect during his Aurora 7 mission in 1962. Apparently his very human reaction to being immersed in the Final Frontier in part caused Carpenter to miss some key objectives during his mission in Earth orbit and even overshoot his landing zone by some 250 miles. Carpenter never flew in space again, despite being one of the top astronauts among the Mercury Seven. It would seem that in those early days of the Space Race, having the Right Stuff did not include getting caught up with the view outside one’s spacecraft window, at least so overtly.

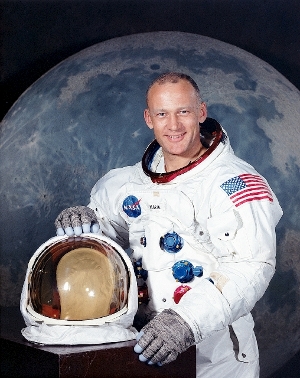

Image: Buzz Aldrin. Credit: NASA

Another item largely missing from Psychology of Space Exploration is the effects on space personnel after they come home from a mission. Edwin “Buzz” Aldrin, who with Neil Armstrong became the first two humans to walk on the surface of the Moon with the Apollo 11 mission in 1969, is one of the earliest examples of publicly displaying the truly human side of being an astronaut.

Although not revealed publicly until 2001 by former NASA flight official Christopher C. Kraft, Jr., in his autobiography Flight: My Life in Mission Control, the real reason Aldrin was not selected to be the first one to step out of the Apollo Lunar Module Eagle onto the Moon was due to the space agency’s personal preference for Armstrong, who Kraft called “reticent, soft-spoken, and heroic.” Aldrin, on the other hand, “was overtly opinionated and ambitious, making it clear within NASA why he thought he should be first [to walk on the Moon].”

Even though Aldrin was a fighter pilot during the Korean War, earned a doctorate in astronautics at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), and played an important role in solving the EVA issues that had plagued most of the Gemini missions and was critical to the success of Apollo and beyond, his lack of following the unspoken code of the Right Stuff kept him from making that historic achievement.

Aldrin would later throw the accepted version of the Right Stuff for astronauts right out the proverbial window when he penned a very candid book titled Return to Earth (Random House, 1973). The first of two autobiographies, the book revealed personal details as had no space explorer before and few since, including the severe depression and alcoholism Aldrin went through after the Apollo 11 mission and his departure from NASA altogether several years later, never to reach the literal heights he accomplished in 1969 or even to fly in space again. Although Aldrin would later recover and become a major advocate of space exploration, he is not even given a mention in Psychology of Space Exploration. In light of what later happened with Nowak and several other astronauts in their post-career lives, I think this is a serious omission from a book that is all about the mental states of space explorers.

The other glaring omission from this work is any discussion of the human reproductive process in space. NASA has been especially squeamish about this particular behavior in the Final Frontier. There is no official report from any space agency with a manned program on the various aspects of reproduction among any of its space explorers, only some rumors and anecdotes of questionable authenticity.

As with so much else regarding the early days of the Space Age, that may not have been an issue with the relatively few (primarily male) astronauts and cosmonauts confined to cramped spacecraft for a matter of days and weeks, but this will certainly change once we have truly long duration missions, space tourism, and non-professionals living permanently off Earth. As with daily life on this planet, there will be situations and issues long before and after the one aspect of human reproduction that is so often focused upon. Unfortunately, outside of some experiments with lower animals, real data on this activity vital to a permanent human presence in the Sol system and beyond is absent.

I recognize that Psychology of Space Exploration is largely a historical perspective on human behavior and interaction in space. As there have been no human births yet in either microgravity conditions or on another world and the other behaviors associated with reproduction are publicly unknown, this work cannot really be faulted for lacking any serious information on the subject. What this does display, however, is how far behind NASA and all other space agencies are in an area which will likely be the determining factor in whether humans expand into the Cosmos or remain confined to Earth.

So Far Along, So Far to Go

What the Psychology of Space Exploration ultimately demonstrates is that despite real and important improvements in how astronauts deal with being in space and the way NASA views and treats them since the days of Project Mercury, we are not fully ready for a manned scientific expedition to Mars, let alone colonizing other worlds.

Staying in low Earth orbit for six months at a stint aboard the ISS as a standard space mission these days gives an incomplete picture of what those who will be spending several years traveling to and from the Red Planet across many millions of miles of space will have to endure and experience. If an emergency arises that requires more than what the mission crew can handle, Earth will likely be a distant blue star for them rather than the friendly globe occupying most of their view which all but the Apollo astronauts have experienced since 1961.

Image: Jerrie Cobb poses next to a Mercury spaceship capsule. Although she never flew in space, Cobb, along with twenty-four other women, underwent physical tests similar to those taken by the Mercury astronauts with the belief that she might become an astronaut trainee. All the women who participated in the program, known as First Lady Astronaut Trainees, were skilled pilots. Dr. Randy Lovelace, a NASA scientist who had conducted the official Mercury program physicals, administered the tests at his private clinic without official NASA sanction. Cobb passed all the training exercises, ranking in the top 2% of all astronaut candidates of both genders. Credit: NASA.

Regarding this view of the shrinking Earth from deep space, the multiple authors of Chapter 4 noted that ISS astronauts took 84.5 percent of the photographs during the mission inspired by their motivation and choices. Most of these images were of our planet moving over 200 miles below their feet. The authors noted how much of an emotional uplift it was for the astronauts to image Earth in their own time and in their own way.

The chapter authors also had this to say about what an expedition to Mars might encounter:

As we begin to plan for interplanetary missions, it is important to consider what types of activities could be substituted. Perhaps the crewmembers best suited to a Mars transit are those individuals who can get a boost to psychological well-being from scientific observations and astronomical imaging. Replacements for the challenge of mastering 800-millimeter photography could also be identified. As humans head beyond low-Earth orbit, crewmembers looking at Earth will only see a pale-blue dot, and then, someday in the far future, they will be too far away to view Earth at all.

Now of course we could prepare and send a crewed spaceship to Mars and back with a fair guarantee of success, both in terms of collecting scientific information on that planet and in the survival of the human explorers, starting today if we so chose to follow that path. The issue, though, is whether we would have a mission of high or low quality (or outright disaster) and if the results of that initial effort of human extension to an alien world would translate into our species moving beyond Earth indefinitely to make the rest of the Cosmos a true home.

The data recorded throughout Psychology of Space Exploration clearly indicate that despite over five decades of direct human expeditions by many hundreds of people, we need much more than just six months to one year at most in a collection of confined spaces repeatedly circling Earth. This will affect not only our journeys and colonization efforts throughout the Sol system but certainly should we go with the concept of a Worldship and its multigenerational crew as a means for our descendants to voyage to other suns and their planets.

This book is an excellent reflection of NASA in its current state and human space exploration in general. As with the agency’s manned space program since the days when the Mercury Seven were first introduced to the world in 1959, we have indeed come a long way in terms of direct space experience, mission durations, gender and ethnic diversity, and understanding and admitting the physiological needs of those men and women who are brave and capable enough to deliberately venture into a realm they and their ancestors did not evolve in and which could destroy them in mere seconds.

Having said all this, what I hope is apparent is that we now need a new book – perhaps one written outside the confines of NASA – which will address in rigorous detail the missing issues I have brought to light in this piece. This request and the subsequent next steps in our species’ expansion into space – which will also eventually take place beyond the organizational borders of NASA – cannot but help to improve our chances of becoming a truly enduring and universal society in a Cosmos where certainty and safety are eventually not guaranteed to beings who remain confined physically and mentally to but one world.

Record-Setting Female Astronaut Takes Command of Space Station

by Tariq Malik, SPACE.com Managing Editor

Date: 15 September 2012 Time: 07:13 PM ET

NASA astronaut Sunita Williams, who holds the record for the longest spaceflight by a woman, took charge of the International Space Station Saturday (Sept. 15), becoming only the second female commander in the orbiting lab’s 14-year history.

Williams took charge of the space station from Russian cosmonaut Gennady Padalka, who is returning to Earth on Sunday after months commanding the outpost’s six-person Expedition 32 crew. Williams launched to the station in July and will command its Expedition 33 crew before returning to Earth in November.

“I would like to thank our [Expedition] 32 crewmates here who have taught us how to live and work in space, and of course to have a lot of fun up in space,” Williams told Padalka during a change of command ceremony. She will officially take charge of the station on Sunday, after Padalka and two crewmates board their Soyuz spacecraft for the trip home.

Full article here:

http://www.space.com/17624-female-astronaut-sunita-williams-commands-station.html

About time!

Space travel and gender as seen in the 1950s:

http://blogs.smithsonianmag.com/paleofuture/2012/10/sex-and-space-travel-predictions-from-the-1950s/

The good Dr. Richardson didn’t include buggering the cabin boys in his “comfort” list.

He was scared enough about man-on-man interaction in these situations, so no surprise there.

I remember my shock at learning that women were not allowed to run in the Boston Marathon until 1972! The few who tried before then were arrested.

I know we have a long way to go in many areas, but at least we are showing signs of improvement compared to even a few decades ago. At least no one flips out any more when a woman goes into space. Ah heck, most people don’t even pay attention to such events. I guess that is progress.

The Overview Effect at 25

Twenty-five years ago, a book argued that those who flew in space experienced a radically altered perception of the Earth.

Jeff Foust talks with Frank White, who wrote about the Overview Effect in 1987 and continues to study it today.

Monday, December 3, 2012

http://www.thespacereview.com/article/2195/1

What Does Space Travel Do to Your Mind? NASA’s Resident Psychiatrist Reveals All.

Esther Inglis-Arkell

Space travel is tough on the human body. But what does it do to the human mind? Gary Beven, a space psychiatrist at NASA, answers our questions about how humans adapt to space, and what we have to do to go to Mars.

Doctor Gary Beven has to have one of the most surprising careers in science. As he puts it, he’s “the fifth full-time NASA civil servant psychiatrist since the beginning of the human space program, the first being hired in the 1980s at the onset of the Space Shuttle Program.”

Becoming an astronaut is a mentally, emotionally, and physically demanding job that’s done at high risk around insanely expensive equipment. It pays to see how this job can be made psychologically easier for everyone involved.

But how does one even start out as a space psychiatrist? I asked Doctor Beven.

Full article here:

http://io9.com/5967408/what-does-space-travel-do-to-your-mind-nasas-resident-psychiatrist-reveals-all#13554082355012

Yet another article where Neil Armstrong is practically worshipped as a demigod who briefly came to Earth (and the Moon) and Buzz Aldrin is put down as a brash, annoying, and spotlight-seeking jerk:

http://www.thespacereview.com/article/2209/1

Yes, Armstrong was a great pilot and astronaut and he become the first man to walk on the Moon – with a little help from the money and resources of the US Government and hundreds of thousands of federal employees, plus a couple of specially-designed spacecraft attached to a really powerful and massive rocket. Armstrong’s nearly relentless ability to brush off the attention he received from that historic feat and remain from humble to silent about it for over four decades after the event are rather impressive in certain ways. He went to rather great lengths in this regard, often going the lawsuit route on anyone who used his likeness or his famous “One small step” phrase without getting his permission first. Armstrong even threatened to sue his barber in 2005 when the guy sold his hair clippings!

However, more than a few have wondered how space exploration and science in general might have benefited if Armstrong had done a bit more publicity for NASA et al. He was already super famous, what harm could a little cheerleading for the science, technology, and agency that put him up there do?

I also noticed how most everyone has skipped over the fact that in 1994 his first wife, Janet, divorced him after 38 years of marriage due to his lack of emotional availability, to closely paraphrase the words she left in a note to him on their kitchen table. The other fact that Armstrong met his second wife, Carol, two years before he and Janet divorced might have had something to do with this as well.

Armstrong’s only other space mission, on Gemini 8 in 1966, practically ended in disaster when the spacecraft’s control jets would not stop firing and was the first to be cut short due to an emergency. He also barely escaped with his life when his Lunar Module trainer went out of control and plunged into the ground. In both of these cases, Armstrong’s bravery and skills were and are still lauded.

I have to wonder, if this happened to Aldrin, would the space fanboys and media have used them against Aldrin to question his skills, integrity, and such? FYI: Armstrong had a number of other flight incidents, but you can read the details if you want to here:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Neil_Armstrong

By the way, Aldrin’s only space mission before Apollo 11 was on the very last Gemini flight, number 12, where his knowledge, skills, and extensive training in a water tank (an idea he was integral in making happen) brought about the only truly successful EVA of the entire Gemini program (Aldrin had handrails, foot restraints, and tethers attached to the exterior of the spacecraft). Along with spacecraft docking, conducting EVAs was critical to the success of Apollo. Gemini 12 also successfully conducted their fourteen assigned experiments and a docking with the Agena booster, something the astronauts on all the previous Gemini missions had problems with to various degrees.

As I stated in this section of my article above, Aldrin had some other pretty impressive pre-NASA astronaut credentials, too, including his stint as a fighter pilot during the Korean War and earning a doctorate in astronautics at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). Aldrin also graduated third in his class from Westpoint military academy in 1951, which he attended after turning down a full scholarship to MIT.

However, as you can also read, everyone from top NASA officials on down have castigated Aldrin for being the opposite of Armstrong in terms of personality. I guess you can only be a spaceman demigod if you kiss the right hindquarters or make sure not to crow about your successes too much. As far as I can tell, Aldrin rightly deserved all of his achievements, including becoming a NASA astronaut, which has never been an easy job to attain and certainly not in the early days of the agency. NASA would not have picked Aldrin to be on such an important mission as Apollo 11 if they did not think he was qualified for the assignment.

For the record, I do not know Aldrin personally nor do I “worship” him. I have very few people in my pantheon of whom I consider to be true heroes. I did meet Aldrin at a lecture he gave at MIT in 2001, where our conversation essentially consisted of “Hello, nice to meet you.” At least he did not come across as aloof as Jim Lovell, who I met at the Boston Museum of Science in 1994, where he was promoting the book that would become the 1995 film Apollo 13. I have heard from more than a few sources that most of the pre-Space Shuttle astronauts range in personality from standoffish to arrogant. At the least they are not the brave, altruistic explorers of the unknown I was given to believe growing up thanks to the NASA publicity machine and the gushing press corps, but a collection of space jocks who were bent on flying space machines to new literal heights for their careers. I know I am generalizing here to a degree, but read some of the more honest biographies and histories on these early astronauts and you will see that I am more on the mark than off.

What bothers me most regarding the reaction to Aldrin is the fact that the ultra macho male dominated world he worked in clearly had a problem that one of their own refused to humbly adorn himself with sackcloth after all of his major accomplishments – which he earned – and then dared to expose the truth that they are human beings! I am sure that Aldrin’s recent stint on Dancing with the Stars and the cameos on 30 Rock and The Big Bang Theory were he actually poked fun at himself have done nothing to help matters in this regard. Hey, I hope I can still dance well enough to be on a television dance program when I am 80 years old!

The other thing that bothers me is that this blog is about the only place I feel “safe” to write about the Apollo 11 astronauts honestly in terms of how I see the situation. No doubt in most other space forums I would be threatened and worse for daring to say anything less than worshipful about Armstrong and uplifting Aldrin for showing his humanity, flaws and all. Though they certainly cheered Aldrin when he punched out that Apollo hoax alcolyte a few years back. :^S

Let us hope as we progress into the 21st Century with a space agency that has more women in it and a much more international view, that attitudes like Aldrin will gain greater respect. Of course the way things are going economically, perhaps we better just hope there will still be a space program in the coming decades!

‘Overview’ is a short film that explores this phenomenon through interviews with five astronauts who have experienced the Overview Effect. The film also features insights from commentators and thinkers on the wider implications and importance of this understanding for society, and our relationship to the environment.

Full article here:

http://moonandback.com/2013/01/15/a-short-film-looks-at-the-overview-effect/