Harry Potter and the Two-Part Blog Post, Pt 1: the Books

by Calvin W. Johnson

I’m delighted to once again host my friend Calvin Johnson, who earlier gave us insights on Battlestar Galactica and Caprica.

(Warning: there be spoilers ahead!)

My wife and I came to Harry Potter in a difficult time. The details of our semi-permanent temporary limbo are unimportant but exiled to a hotel room, we began to read aloud to each other. We read Harry Potter.

My wife and I came to Harry Potter in a difficult time. The details of our semi-permanent temporary limbo are unimportant but exiled to a hotel room, we began to read aloud to each other. We read Harry Potter.

Having read all of Harry Potter and several other series, I can sum up the reason for the renaissance of young adult literature in a single word: narrative. Modern and postmodern literary fiction, which Annie Dillard has termed the ‘fiction of surfaces,’ has all but abandoned narrative drive. But page-turning narrative and crisp characterization still abounds in young adult fiction.

Rowling showcases many of the virtues of YA books. She writes narratives that keep the reader wanting to know what happens next? In this she has mastered a key skill, namely creating plot twists that surprise but in retrospect make perfect sense, misdirecting the reader while dropping in hints that you only later recognize as pointing to the true solution. In The Prisoner of Azkaban she did this beautifully, allowing the reader to congratulate himself on figuring out that (spoilers) Remus Lupin was a werewolf, so much so that one completely misses that the true villain was Ron Weasley’s pet rat. And in The Deathly Hallows we finally learn the key to Snape, and why Dumbledore believed Snape had truly turned against Voldemort (that’s not a spoiler, we had to find out). In retrospect the solution appears obvious — and once she reveals it, Rowling bludgeons the reader for twenty pages where a couple of poignant paragraphs would have served — but only a few readers guessed in advance.

Rowling also writes vivid and memorable, if generally one-dimensional characters. Nothing wrong with such characters; Dickens created dozens of them. Of course, Rowling also mistakenly thinks that hiding information from the reader (example: Snape) counts for character complexity. On occasion, however, she manages to suggest true subtlety: by the end of The Deathly Hallows she convinces us that Dumbledore is loving and compassionate, and arrogant and manipulative. Real people are often both, and it is only after his (spoiler) death that he truly came to life.

Rowling also has her flaws. It’s important to keep in mind that she was almost literally the overnight success who came out of nowhere. She wasn’t the product of an MFA program, hadn’t toiled for years writing a stack of unsold novels. The former kept her free from literary pretensions but it also means her self-taught craft is full of amateur habits.

Although I do not begrudge Rowling her enormous success, I do selfishly wish the Harry Potter craze had come later. Around the time The Prisoner of Azkaban came out, the Harry Potter phenomenon exploded and simultaneously the craftsmanship of the novels plummeted.

The Prisoner of Azkaban is the best book in the series; Rowling had mastered this world, yet her plots and prose are still relatively lean. But the next books bloat grotesquely. Rowling’s gift for plotting became a curse, as her books festered with subplots and sub-sub-plots. Furthermore, the prose became systematically clunkier and cluttered with lazy punctuation.

The Prisoner of Azkaban is the best book in the series; Rowling had mastered this world, yet her plots and prose are still relatively lean. But the next books bloat grotesquely. Rowling’s gift for plotting became a curse, as her books festered with subplots and sub-sub-plots. Furthermore, the prose became systematically clunkier and cluttered with lazy punctuation.

I suspect what happened is this: in the early books Rowling’s editors helped shape the books into the brisk, enjoyable narratives they are. This is the job of an editor as few writers, particularly beginning writers, can pull off a novel that does not need judicious revision. But I suspect that as the Harry Potter books became fabulously successful, her agent and editors became reluctant to rein her in, fearful of killing the goose that laid the golden bestsellers. Oh, I’m sure they worked with her, sure that Rowling wrote and rewrote. Nonetheless, the books after Prisoner are flabby affairs that would have benefited immensely from ruthless, savage pruning.

Take, for example, The Order of the Phoenix. It has, easily, the best villain of the entire series, Dolores Umbridge. Lord Voldemort is a sniggering cartoon of evil. But Umbridge, a nanny-state bureaucrat gone bad, is the very model for Hannah Arendt’s banality of evil. And the story of Harry’s resistance against Umbridge and the rise of Dumbledore’s Army is a cracking good story.

The rest of the novel, however, drowns under teenage hormones run amok and Quidditch jealousies and a completely irrelevant subplot devoted to Hagrid’s giant half-brother Grawp. You could remove Grawp from this and every subsequent novel and lose almost nothing. It’s nothing against Grawp. I like Grawp. But too many, too detailed subplots hurt the book.

On top of this, Rowling’s native prose is… well… clunky: relying far too much — far too much! — on ellipses, colons, semi-colons, dashes, and so on. This becomes stick-in-your-eye obvious when read aloud. Compare a random page from the first three novels with one from the last three; you’ll find the number of ellipses and semi-colons rises dramatically. And I’ll tell you this: adding ellipses… and semi-colons — not to mention colons and dashes — in large quantities does not improve the quality of prose. Once again, the later editing process failed both Rowling and her readers.

So why was Harry Potter so massively successful?

Part of it was, as always, timing. Audiences were tired of postmodern fictions of surfaces. She offered an engrossing plot. But in addition, the underlying themes of the novels touched readers, as they do in all the best fantasies. J. R. R. Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings is drenched in grief for a lost world. The novels of C. S. Lewis were all about how we lie to ourselves. And the Harry Potter books touched a wire to the hearts of young adults and also of us adult adults:

The loneliness of the modern world.

Harry is cast from the central cliché of young adult novels, an orphan raised by resentful, stingy relatives. But he isn’t the only loner. Hermione, isolated by her talents, her painfully sharp perception, and her muggle origins; Ron, lost in his family as a relatively talentless middle child.

This theme isn’t new at all but once you pull at this thread, you realize that nearly all of the characters are tremendously lonely: Hagrid, whose enormous heart can only find an outlet in loving killer dragons, car-sized spiders, and other monstrous creatures; Dumbledore himself, immensely talented but, we learn, always haunted by secrets in his past; Neville Longbottom, the fat, teased son of parents tortured into insanity, pecked at by his strict grandmother; weird Luna Lovegood who happily hangs out with Harry because “it’s almost like having a friend.”

Nearly everyone is an exile. Sirius Black is wrongly branded a murderer. Remus Lupin is a kind-hearted werewolf. And in the end we learn just how impossibly tormented Snape is, and why as penance he takes on the lonely life of a double spy, trusted and liked by no one.

Even the villains are cursed to loneliness. Draco Malfoy, bullied by his father, bullies others in response. Mad-eye Moody is impersonated by a Death Eater, the rejected son of an ambitious politician. And Voldemort’s quest to ‘eat Death’ itself arises out of his abandonment at an early age. Although Voldemort ends up a cartoon villain, Rowling makes his journey to the dark side more believable than did Lucas with Darth Vader.

Indeed, Rowling gets right what George Lucas got wrong. As Athena has written eloquently in her essay, We Must Love One Another or Die, the fake-Buddhist Jedi code requires renouncing emotional connection to other people. Lucas’ muddled concept led to the cinematic disasters of Star Wars: Episodes I-III. But in Harry Potter, the ones who learn to love are the ones who triumph. Harry is originally saved from Voldemort’s killing curse by the love of his mother. And it is not through spells or wands so much as Harry’s connection with Hermione, Ron, Hagrid, Ginny, and so many others, that he triumphs. His friends, in turn, grow under his wing. Witness Neville’s transformation over the course of the series from a dull joke into a sleek, bold resistance fighter.

Through Harry Potter, Rowling teaches that love is more important than credentials. While Death Eaters worship the authority of their Dark Lord and murder muggles and mudbloods, Harry easily and intuitively befriends and protects the marginalized, the Nevilles, the Lunas, the Dobbies, and is unafraid to defy the powerful Minister of Magic.

And in these days, when people denounce others as Nazis and communists and religious terrorists, when we fret over immigration and the cultural purity of nations — Rowling tries to tell us that compassion triumphs over blood, that our choices, not our origins, are what best define us; that it is love, not for those like us but for those different from us, that is the most powerful magic of all.

Next time: the movies.

Spoiler policy: I’d ask that while the first six books are open for discussion, commenters not give away major plot twists in the last book.

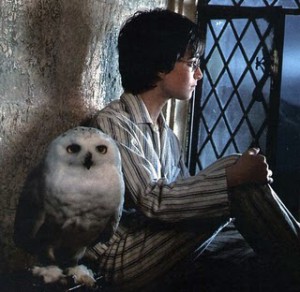

Images: 1st, Harry Potter (Daniel Radcliffe) and his familiar, Hedwig; 2nd, Professor Minerva McGonagall (Maggie Smith), who would have pruned Rowling’s books vigorously; 3rd, Harry in a Sam Beckett setting and mood; 4th, Remus Lupin (David Thewlis) and Sirius Black (Gary Oldman), the feral loners who are nevertheless Harry’s devoted kith and kin.

“I suspect what happened is this: in the early books Rowling’s editors helped shape the books into the brisk, enjoyable narratives they are… But I suspect that as the Harry Potter books became fabulously successful, her agent and editors became reluctant to rein her in”

This is pretty much the reason I stopped reading after Order of the Phoenix. Prisoner of Azkaban was sharp, tight and had enough plot twists to make your head spin. And some wonderful moments–like when Lupin wouldn’t let Harry face the boggart in class. After that, the books just felt so flappy and bloated that I couldn’t keep track of what was going on and to whom.

I know two people having the same opinion doesn’t make it objectivly ‘right’, but it’s good to know I’m not alone.

Good point about all the heroes being outsiders. I hadn’t really noticed that, but it’s very true. And probably, as you say, one of the keys to the books’ success. I mean, we all feel like outsiders when we’re young adults, don’t we?

Do you know, I find it interesting to note that the original Jedi Code was actually the following:

“Emotion, yet peace.

Ignorance, yet knowledge.

Passion, yet serenity.

Chaos, yet harmony.

Death, yet the Force.”

And that, somehow, it got transformed into this:

“There is no emotion, there is peace.

There is no ignorance, there is knowledge.

There is no passion, there is serenity.

(There is no chaos, there is harmony.)

There is no death, there is the Force. ”

It’s almost as though, over the years, the Jedi grew in self-imposed isolationism, to the point that they had ceased to be in-tune with the world around them, in fact creating the conditions for the rise of the Sith, for the downfall of the Republic and of the Jedi Order. To draw a parallel with the Potterverse, it’s as though they had forgotten to act like Harry Potter and his friends, for whom attachments are indeed a source of strength.

Do you know, this actually reminds me of Aragorn’s last battle cry at the end of The Return of the King:

“A day may come when the courage of men fails, when we forsake our friends and break all bonds of fellowship, but it is not this day. An hour of woes and shattered shields, when the age of men comes crashing down! But it is not this day! This day we fight! By all that you hold dear on this good Earth, I bid you stand, Men of the West!”

For when we forsake our bonds of fellowship, we become obsessed by greed and power plays, and forget what makes us human. Boromir actually paid the highest price for such hubris.

Oh, and on another note, I do find that the Potterverse could be construed as yet another reinterpretation of the Arthurian cycle, what with the Arthur-Guinevere-Lancelot triad being reincarnated into the Harry-Hermione-Ron trio, with Dumbledore’s Army standing in for the Knights of the Round Table, and with the magical sword of Godric Gryffindor (coming to the worthy in their time of need) representing a newer version of the Pendragon’s Excalibur.

Damn, but we’re all going in circles, now, aren’t we?

Cheers,

Eloise 🙂

Dylan, as Calvin knows, I haven’t read any of the Potter books and only saw the first 3 films plus the latest one. Prisoner of Azkaban was the best hands down, which is partly the book itself (from what I’m told), partly Cuarón’s helming. The other directors genuflected to Rowling and the fans as much as the editors did, with predictable results. The picture of the books lined up in Wikipedia speaks for itself regarding the bloat: #4-7 are each the size of the first 3 put together. I didn’t read the Potter books because I dislike both messianic fables (aka Chosen Ones) and arbitrary magic. But more of this when we discuss the films.

Eloise, yes, round the Round Table! *laughs* However, I think all your points are accurate. By the way, if you’re curious, there’s a compelling one-to-one mapping between The Silmarillion and Babylon 5. Here are a couple of links:

http://www.jumpnow.de/b5lotr/index.php?op=silm

http://www.katspace.org/fandom/b5/myth1/

I didn’t realize there was an original and a “debased” version of the Jedi code. Of course, this is the case for practically all faith tenets. And the cynic in me wonders if fans or insiders retrofitted the code when its toxic vacuity became obvious.

Good points all. The comparison to the Arthurian cycle is interesting. Of course, when one has a finite number of archetypes it’s not too hard to find similarities. And I must admit, though my training is in physics, after a while making these kind of literary analyses becomes an automatic habit. Once, for a seminar on literature and science, I wrote a joking essay interpreting Moby-Dick using spontaneous symmetry breaking and critical-point behavior. The literature professor loved it a bit too much.

Dylan, another ‘tell’ of loose editing: in the later books it’s inconsistent whether or not one capitalizes after a colon. Usually copy-editors are fastidious about these kinds of things and even have definite style manuals dictating the choice. Even when I get galleys of scientific papers, the copy-editor has carefully checked all this (usually). While this in of itself is not important, it suggests to me someone was asleep at the wheel.

Regarding bloat: After the first 4 books, I extrapolated the growth and predicted that the 7th book would be between 10,000 and 13,000 pages in length. Unsurprisingly, even Rowling saturated, but there was a very nice geometric growth curve; it’s almost perfect in the first 3.

The mythic borrowings in Harry Potter are fairly transparent: Middle Earth, the Arthurian legends, Narnia… parts of the Bible, a bit of Homer… mix, add British boarding school shenanigans, et voilà!

Can I see that paper? Again, the cynic in me isn’t surprised your lit prof loved it. Appropriation of QM valorizes the hermeneutics… *laughs*

Thanks, Calvin! I am happy to see I wasn’t the only one suffering from these ellipses. The further along, the more ellipses there seemed to be… until… everything… was… drowining…. in… ellipses…

Thanks for sharing this, Calvin. 🙂 The comparison of certain themes in Harry Potter to those in the Lord of the Rings, especially that of the bonds of friendship and love standing as strength instead of being called weakness — especially as captured in Aragorn’s powerful battle cry — as the changed (degenerated) Jedi Code suggests, is a good one. I also find the series borrowing from the Arthurian legends and other myths interesting; the similarities in those bring to mind the timeless relevance of the abovementioned theme alongside others.

Aside from that, I didn’t care for the excessive overuse of ellipses, either…

Calvin, I loved this essay (laughed at your paragraph on dashes… and ellipses–not to mention colons: furthermore, you covered even semicolons; this is a triumph, in my book).

I was especially moved by what you said about the loneliness of the characters; I had never really articulated it for myself, and as you went through and described the lonelinesses of each of the characters, I could really see it. They were great encapsulations of the characters, too.

Thanks! I’m working on Part 2: The Movie(s)!